Capriotti won second place in globally renowned Sony World Photography Awards for “Terra Nullius”

“There was this untold history. Everybody knows Canada as the place for multiculturalism where everybody is welcome, where you know you can start a new life, where you can keep your own traditions. But we do that on the land that belongs to somebody else." - Giovanni Capriotti, Media & Communication Studies instructor

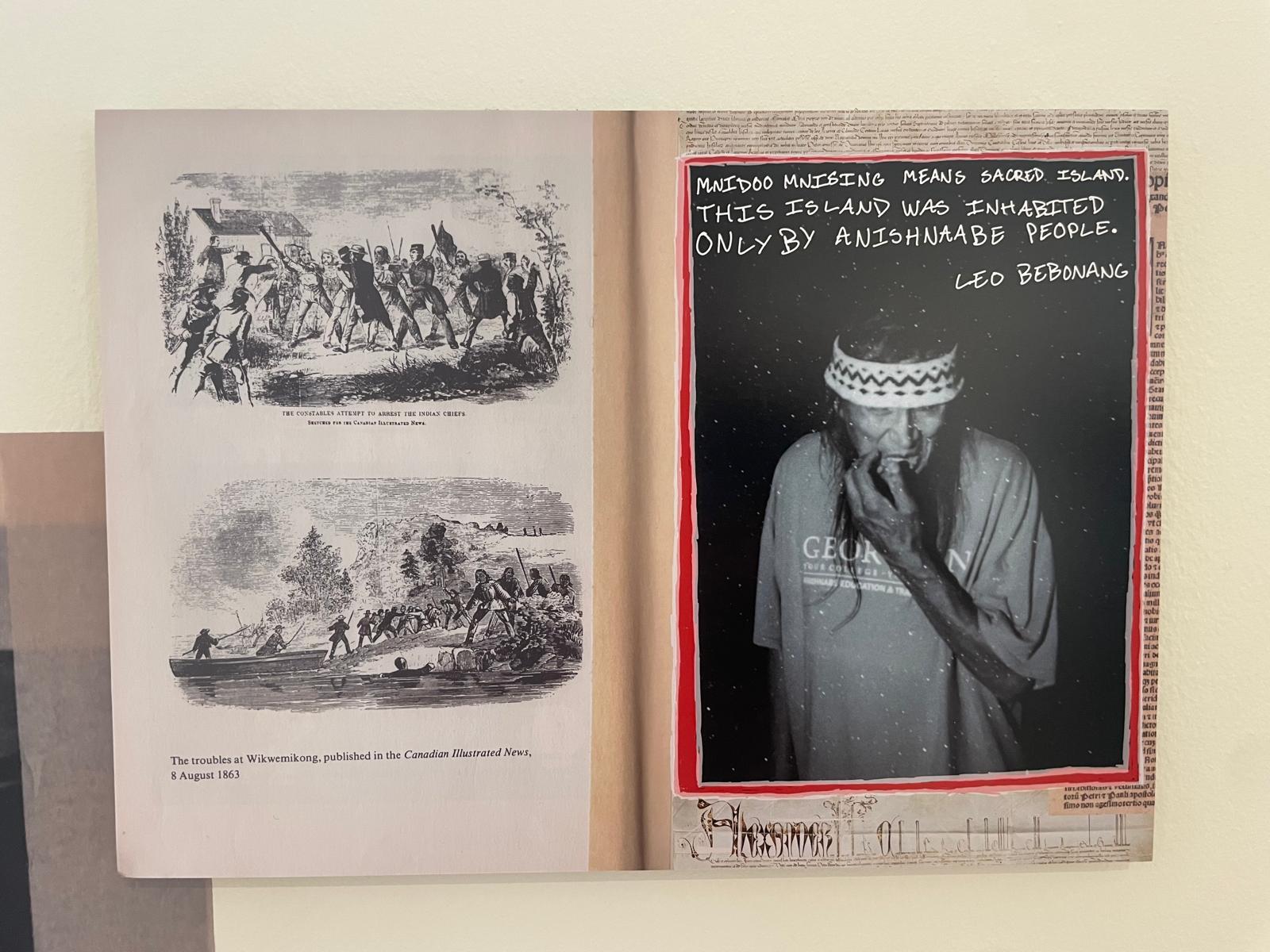

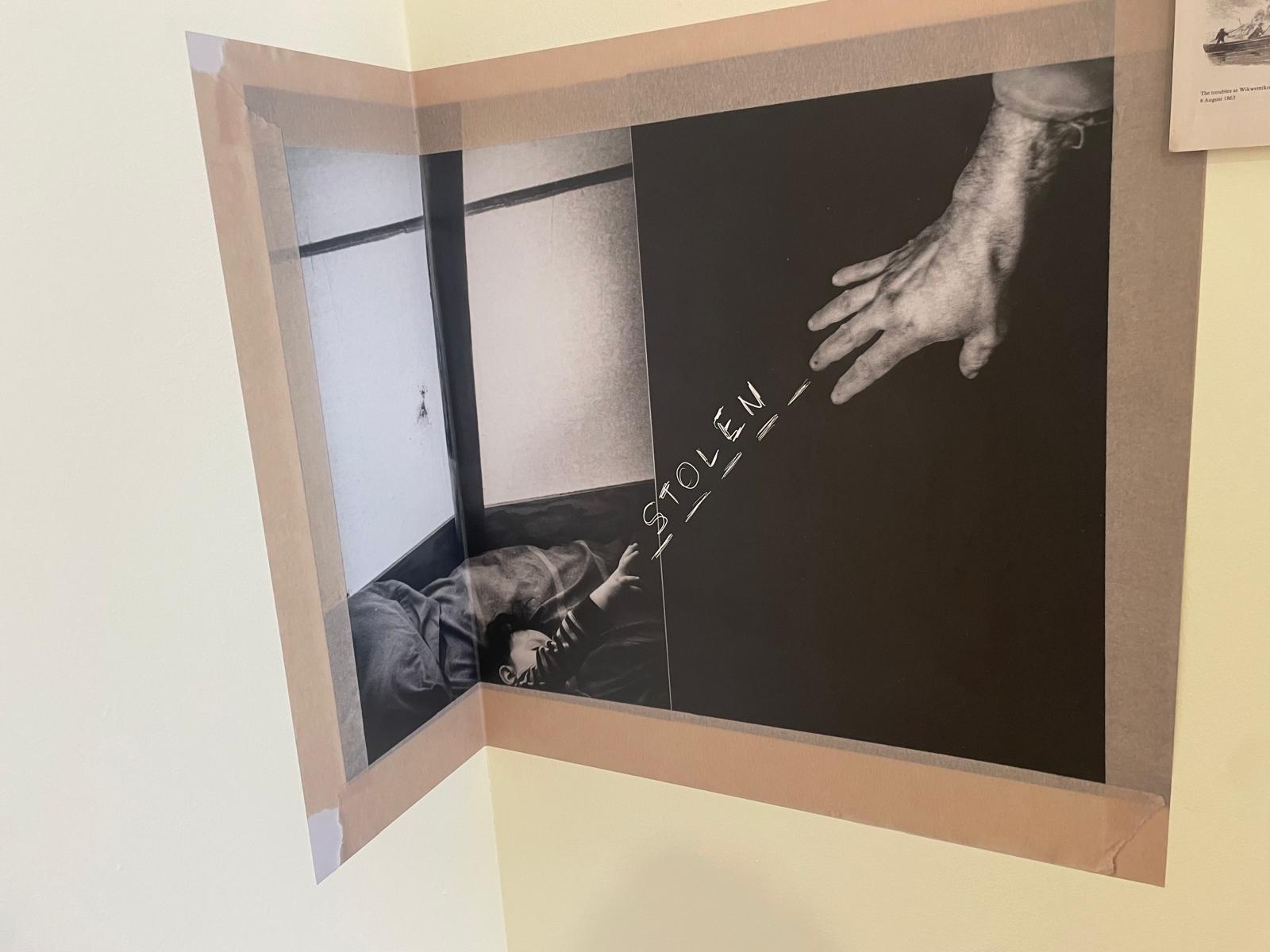

Terra Nullius is the Latin phrase for “nobody’s land.” It’s a colonial construct that has been used to describe land that’s seen as “unclaimed” or “uncivilized” – land that was forcibly taken from its Indigenous inhabitants, including in Canada.

Terra Nullius is also the name of an award-winning photography project by University of Guelph-Humber (U of GH) Media & Communication Studies instructor Giovanni Capriotti. He gathered archives, created images, and made collages with photos he collected. This project won him a second-place Sony World Photography Award in the Perspectives category in April 2025. He flew to London, England to attend the gala where he received the honour, as well as went to the special exhibition’s opening where his work was displayed, which he called “a great experience.”

“I don’t do it for the awards,” Capriotti said of his photojournalism. “If we only got out of the house to shoot [photos] for awards, it would deceive the purpose of what we do,” he explained.

Capriotti moved to Canada in 2009 from Rome, Italy. When he immigrated, he knew nothing of Indigenous culture and history in Canada, which was not uncommon for people from Europe. But that started to change for him in 2010 during a journey to Manitoulin Island.

While driving across the Trans-Canada Highway with a friend from Italy, the pair pulled over for gas. While paying, the cashier asked Capriotti if he was Indigenous, and began explaining Indian status cards, tax policies within reserves, and more, which sparked a conversation. A couple of days later, after “falling in love” with Manitoulin Island, Capriotti shared what he learned with his wife, realizing just how little he knew about Indigenous peoples in Canada – and he wanted to know more.

As time went on, he returned to the island many times; he visited Manitoulin Island every weekend for three years and also spent longer periods of time there (up to a month) in order to get to know the Indigenous community, speak with elders, hear their stories, understand their history, and really immerse himself. This time was enlightening for him.

“There was this untold history. Everybody knows Canada as the place for multiculturalism where everybody is welcome, where you know you can start a new life, where you can keep your own traditions. But we do that on the land that belongs to somebody else,” Capriotti said.

This is when he began Terra Nullius, a project he worked on for more than a decade. He said he feels that photographers can be in a position of power, capturing the subject as they see fit. But he did not want Terra Nullius to be this way; he wanted to remove the power imbalance and listen to Indigenous voices to learn from them and collaborate with them.

With rich traditions and beautiful cultures, but also a history fraught with intergenerational trauma including through colonialization, residential schools, missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, and more, Capriotti wanted to amplify the stories of Indigenous communities in Canada and “confront colonial erasure” with guidance from local elders. While collaborating with the Indigenous communities featured in the piece, he collected hours of recordings and notes to document his learning and to capture those important perspectives. Reconnecting Indigenous participants to their ancestral roots and traditions helped these communities heal from intergenerational trauma.

“As an immigrant, the photographer’s aim is to confront colonial erasure, amplify Indigenous voices and advocate for self-determination – challenging the lens that dismisses these injustices as mere footnotes of progress,” Capriotti’s description for Terra Nullius read.

Furthermore, he was motivated to craft Terra Nullius because even through reconciliation efforts, Indigenous peoples still don’t have “the self-determination they deserve,” on their ancestral lands. Winning the award allowed for Capriotti to share their stories through visuals on the global stage and achieve his aim to amplify those voices and stories.

“I have the best job ever. I get to meet people, and I get to go to all these places, but it's always on somebody else's land,” he noted.

Capriotti brings the insights he gained from creating Terra Nullius into the classroom, sharing them with his students at U of GH. He strives to teach students a structure that includes a work plan, shooting, editing, sequencing, and the visual communication implications of these actions, though he stressed that he’s always open to how students adjust the process to their personal approach. Capriotti added that this is a dual form of learning: for them as students and for himself as an instructor.

“I try to teach them, always coming from my professional experience, to create something that is always leaving the viewership with a question that can be answered through personal research, like through reading a book, to looking at some more imagery, to reading the news,” he said. “I am someone who is always learning through every process that I go through and I'm bringing it back to the class.”

Capriotti has previously won several accolades, including a World Press Photo award and Pictures of the Year International award. He said that receiving the honour of a Sony World Photography Award and being recognized on a global scale gives visibility and justice to the countless days and hours that photographers like himself spend on long-term projects, and he is grateful for the recognition.